Allan Horton has borne ultimate witness to some tasty chapters of King’s Cross history

After two and a half decades watching over the yard, Allan Horton has borne ultimate witness to some tasty chapters of King’s Cross history. Tom Kihl takes a walk with him.

Some are born glamorous, some achieve glamour, and some have glamour thrust upon them. For an unassuming security supervisor working for parcel company DHL in 1994, Allan Horton’s career path has featured very much of a glam thrust, including a stream of pop stars, outrageous partygoers, world class-architects, chefs and chic boutique owners.

“I was originally moved over here because there was a problem with people dumping rubbish,” he recalls, of how this odyssey first began. Although the King’s Cross Goods Yard has long been abandoned by the rail and waterway companies for whom it was elaborately first constructed, it was still a working depot, filled with all manner of industry. “Oh, it certainly wasn’t deserted,” says Allan. “You had Charles Wells the brewery from Bedford over in the Western Transit Shed, truckloads of first editions of newspapers would arrive in the early hours each day, Fortnum & Mason parked all their delivery vans here, Metroline had buses, Pickfords stored antiques, there was a lighting company for big movies, and cement mixers driving in all day to get diesel.”

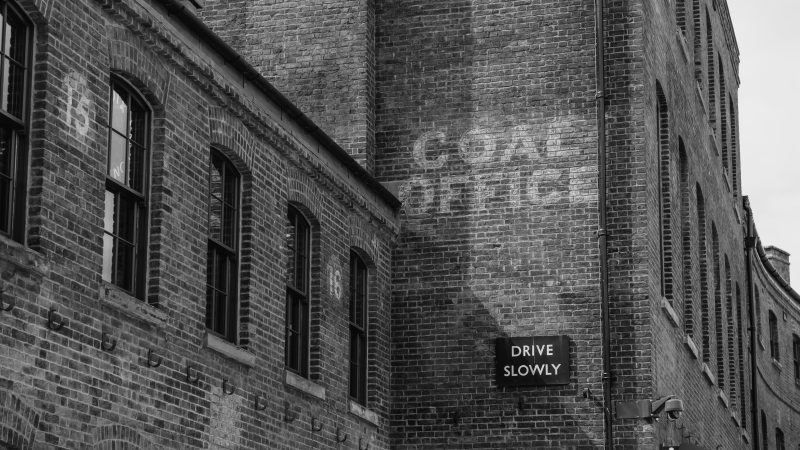

From coal store to chic ateliers

We’re standing atop the Western Coal Drops, where tonnes of the black stuff were once tipped out of rolling stock for distribution by horse and cart below. Today, a couple of well-dressed girls peruse the new season’s frocks at BA&SH through a window beside us, while across the way, staff are busy laying tables for the lunchtime service at Barrafina. “All these were lockups,” says Allan, with a sweeping motion towards today’s stylish emporia of Blackhorse Lane Ateliers and Kitchen Provisions. “Everyone helped one another out; there was a lovely little community spirit. I once got some wood from one guy, then took it along to another who turned it into a worktop for my kitchen, no problem. What’s nice is to see that the same spirit has returned today. Everybody here talks, it feels like a real town square.”

A mecca for the capital’s all-night party people

Back then it wasn’t just engine repair shops and friendly cabinetmakers, though, “we had a go-cart track where the new bit of UAL is now, there was a golf range down the bottom, and then in the evenings you had the nightclubs.” Ah yes, Allan’s arrival to secure this rambling collection of lockups, sports attractions and logistics businesses also coincided with the rise of the warehouse we’re standing next to into London’s legendary multi-room 3000-capacity rave space, Bagley’s. As the weekly crowds swelled, an owner of one of the road haulage firm based in the yard, named Billy Reilly, speculatively opened a smaller venue called The Cross in some nearby arches, and the yard was well on the way to rivalling the West End as a draw for London’s all-night party people. “Billy’s dad was a mechanic who had a little lockup here doing car repairs,” remembers Allan. “A few years later, Billy was using the space to park all his Jaguars.”

As well as the flash motors, the explosion of nightlife here brought a fair bit of colour to Allan’s routine, even though the venues brought their own security teams in to manage the thousands of clubbers. Having so many exuberant people on the site actually made it a far safer place at night, when the main problem became “amorous couples sneaking off behind a lorry,” Allan smiles, an eyebrow lifting. “We had CCTV cameras everywhere, though, and they’d always get caught by patrolling bouncers. Then on Sunday afternoons the Australians would come for this big drinking party called The Church, which was famous for the girls taking their tops off. We also had the Red Hot Chili Peppers play a gig, Prince came to play a secret party, Madonna shot a video in the room that was used as a rollerdisco and Grace Jones played on a big stage over there when The Cross put on a big bank holiday festival,” he says, pointing towards the old rail viaduct.

“You have the land, you have Allan…”

As glitzy as this celeb-magnet had become, a key part of the magic was always the rawness of the post-industrial urban wasteland in which the clubs existed, somehow getting away with making an all-night racket for joyously drug-addled youth right in the middle of the capital. It wasn’t just the neighbourhood’s notorious backstreets, bristling with their dealers and hookers, that gave it all an edge. The crumbling coal drops, with an entire section burned out from a big fire back in the 1980s, were a fairly insalubrious place in which to fall about with thousands of strangers until the early hours. “It was all pretty makeshift, as they were always preparing to move out for the development of the whole site,” says Allan. “Many of the Bagley’s toilets just had a pipe where raw sewerage was running down straight into the Victorian drains.” Yet in the end, it was the clubs that were the last businesses to move out, having outstayed their original date of execution by some years while planners wrangled. Argent were winners of the eventual contract to revitalise the whole site. “I came with the land,” declares Allan. “It was like, you have the land, you have Allan. I was the only one. I felt like one of the buildings, part of the heritage.”

For eight years, what is today’s Coal Drops Yard sat silent and empty, as the phased King’s Cross redevelopment focused first around Granary, Pancras and Cubitt Squares. The quiet brought back many of the old challenges. “We’d have squatters throw illegal raves that took a trip to the high court to have evicted. People would get through the fence, and you’d see the girls wandering up here with the blokes. We’d shout out so they knew someone was watching them, then go picking up needles and all that. We were supposed to report everything to the police, but it became easier just to go and have a chat. The regular squatters used to be nice as pie. I got on great with them. We’d say, ‘come on lads, you know you can’t stay here, but see you again same time tomorrow. Just make sure you’re not here when the demolition starts’.”

A proud custodian of a London transformed

These days, Allan proudly guides all the new starters around the site, pointing out historic features such as the black bricks that show where the Plimsoll Viaduct used to run across Regent’s Canal, or how original wooden beams that once looked down on Bagley’s main dancefloor were moved to replace ones in the burned-out section of the very same building. He’s a fan of Thomas Heatherwick’s kissing roofs, having seen the structure conceptualised, then realised, on his patch – and all without adding any loading pressure to the listed Victorian-era structures below.

“I’ve seen it every step of the way,” he says proudly. “Been in every building as it’s going up, all the way to the topping out. I just love the place. And you know, it’s been a real pleasure to see a lot of the people who’ve come in to work here over the years come to love it as well.”

This article first appeared in the Spring 2020 edition of King’s Cross Quarterly magazine. Read more about the people and stories that make King’s Cross.